The journey began in January of 1982, in the most abrupt way any journey could begin. Aliza Schwartz, after two years of fighting cancer died at age 54. This sad event started the Schwartz family on a long voyage, ending June 17, 1995, with the arrival of the Aliza, dock side at Newport Marina. The twin towers of the World Trade Center in downtown New York City stood watch in the distance. On board were Moshe, Zipora (Zipy) and Efraim Schwartz.

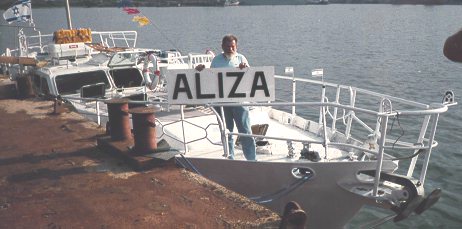

Moshe Schwartz and Aliza in upper New York bay, with downtown Manhattan and the World Trade Center towers.

We had a major problem on our hands from the beginning. Having just lost his wife, Dad, without a purpose in life, was going downhill fast. We started to look for the right things to do. It didn’t take long to figure it out, Dad’s life needed a new focus. Dad and I had always dreamt of building a yacht. So a yacht it would be… the dream of adventure in our lives. We had only to choose our path.

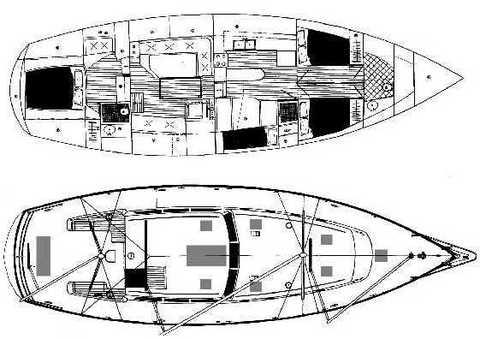

The selection process took almost a year. Dad and I visited every boat show in sight and looked at every boating magazine. At first we looked to purchase a pre-built hull from various manufacturers and ship it to Israel, where Dad could finish the interior. However, after looking at many hull designs, we decided we would build a steel sailing yacht from blueprints. There were many reasons for the decision to build in steel. The more books and articles I read, the more I found that for the cruising life, the experts agreed that steel offers the best long-term material. The model we chose was designed by Bruce Roberts and named the Roberts 53G. The selection of the Roberts was primarily based on the lines and amenities of the original design. We knew we could modify the interior to our liking and needs. Also the “pilot house” layout offered weather protection and a second inside steering station. We were not big on the “macho” idea of standing out in the storm and piloting the yacht. We wanted to have the option to pilot the yacht from the protection of a pilot house, with the radar showing us what we could not see and the auto pilot steering us to the next GPS waypoint. The interior changes needed to accommodate our three families… my sister’s and my own, each with two kids, and my father in the aft cabin. We had evaluated the Roberts 53G study plans and decided it was a go.

Aliza final design modifications.

One month into the project, Dad phoned from Israel to thank me. He was excited again. He also thanked me for convincing him to go with the Roberts design. Originally, he thought he would build a 35 or 44 footer to gain experience and then build a BIG boat later. He said, as everything was new to him, it was still the same challenge to build a 35, 44, or 54-foot yacht. Aside from material cost, the end result is very different, both in live-aboard quality, and ability to travel safely around the world. Our design is 53’10” practically 54 foot long.

Moshe Schwartz is pouring hot lead into Aliza’s keel. This is 6 Tons of Ballast required for Aliza.

During the next seven years, our production and procurement process came to life. The purchasing manager/systems designer (myself) was very busy reading every article written about boat building and outfitting. We were moving forward and making decisions that would affect the quality and length of our lives. During those long years when the production manager/only worker (Dad) was making the hull, I was designing the electrical system, refrigeration system, and the sailing information system. Yes, there is even a network on board where the dual GPS systems exchange information between the radar, autopilot, wind/depth/speed instrument and the navigation computer.

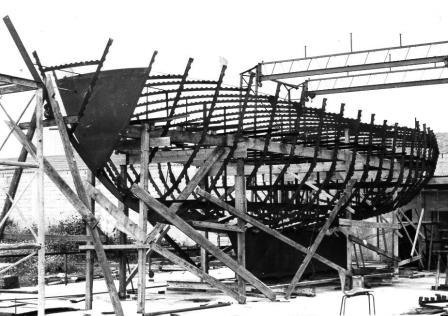

Aliza is on her keel showing all ribs and one watertight bulkhead. She is waiting for the steel plates to be welded to the ribs.

Every critical system is redundant. Safety came first, the main reason being worst case scenario planning. (My “what if” questions drove my father crazy.) As I thought of my twelve years of problem solving at the escalation center, where “everything that could go wrong, did,” my father needed an introduction to Murphy’s Laws. It was an uphill battle, but finally, the end result was on the side of safety.

I thought, for two people, with practically zero sailing experience, to attempt building and sailing a 54′ yacht from Israel to America on her maiden voyage, was reason enough not to complicate things by cutting corners on safety issues.

During the build/weld/grind phase, Dad had a number of situations where he was introduced to Murphy and saw what he later described as “Aliza watching over us”. As Dad was working alone, and as he was working so fast, he did cut some corners a number of times. At one point he almost lost an eye as he was grinding without safety glasses. Another time he admitted himself to the hospital with 3rd degree burn on his leg as his pants caught on fire while he was welding. It seems that in the excitement and enthusiasm of his work, he hadn’t noticed the fire until it was too late. All of these “events”, as my father dismissed them, made Zipy and myself very worried. We had asked him to take it easy and slow down. (This is the most difficult thing to do with Dad. He has only one speed – Full Steam Ahead)

During that time we had visited a sister ship. We discovered that below deck at noon on a sunny day, it needed to have the electric lights on, due to lack of natural lighting (portholes and hatches). For this reason, we changed the original Roberts design and added six more hatches for more light and ventilation. We also added a very large hatch in the center of the pilothouse in order to allow the engine, and later the generator set, to be installed. We really did not understand the logic of building the yacht around the engine, as it was too large and heavy to go through the companionway or any other opening we could see in the plans.

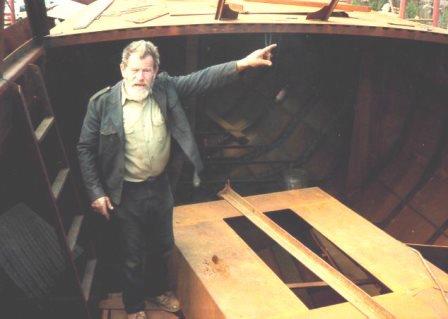

Moshe is standing inside the hull and next to him is the frame of the lower keel fuel tank.

When the hull was completed, Dad started the interior woodwork. He used American oak which is light in color, instead of the traditional teak and other dark woods. These darker woods contributed to somewhat of a claustrophobic feeling.

Moshe is standing inside Aliza, in the door to the Starboard forward cabin.

It became time to begin the wiring. Aliza is wired in 24 volts DC for all marine devices and instruments and 110 volts AC for lights and convenience i.e.: microwave, coffee – maker, TV, VCR and stereo. The 110 volt AC is provided by two 2500-watt inverters. The outlets in the three heads, kitchen and work area are done with GFI (ground fault interrupt) circuits. It was a tedious job to route each wire and secure it with tie wraps every few inches. In order to avoid the chaffing problem due to vibration, each tie-down was wrapped with a piece of rubber, to avoid contact between the steel hull and the electrical cable.

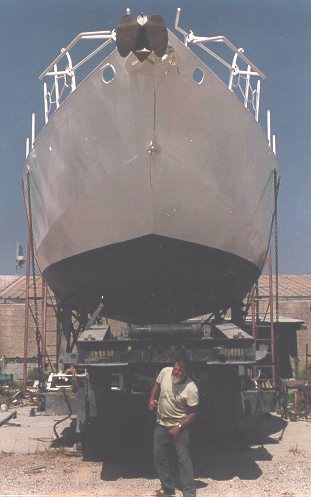

Moshe is about to move Aliza on his own after we loaded her on the trailer. It was Friday and we were waiting for the Police and Electrical Power company people to come and escort us on our trip to the Isreali Shipyard.

After seven long years, Aliza was ready for her the big day. The first change of scene was a five-mile trip from the building site to the waters of the Mediterranean Sea. It was a busy Friday morning when the crane arrived and we loaded her on the flatbed of a tractor-trailer.

By noon we were ready to go. However, our procession had to wait for the afternoon traffic to lighten up and for our escort to arrive. Included in the convoy were two police cars, two public utility cars, two electric company cars, one telephone company technician car and one car with radio contact to the 18 wheeler’s driver. The scout’s job was to alert the driver by radio, warning him of problems on the route and directing him on his trip. The Schwartz family added two more cars to the convoy. There were also two people from the public utility company riding atop Aliza, making sure all electrical cables stayed clear, topside.

Aliza is leaving the “Schwartz Marine Boat Yard” and moving on the road to the launch site at the Isreali Shipyard.

It was some sight to see Aliza moving. The yacht looked big out of the water, with her deep keel and wide beam. All traffic was stopped by the police as we moved at between three and five miles an hour on our way to the Israeli Shipyard where she would be launched. I was riding in the forward car, taking video of the trip. Finally we arrived at the yard and left her for the weekend. (No workers work on Friday night, or Saturday, in Israel.) We were there again on Sunday to watch the crane operator take her off the trailer and set her on the ground. She needed a couple of weeks of prep work before the launch.

We were working fourteen to sixteen-hour-days getting Aliza ready by August 27, the date of the official celebration. The time was spent putting on most of the above-deck structures. These were left off, because of height restrictions on the road from the building site to the shipyard.

The long awaited day had arrived and we were all excited. The electrical systems were connected; seacocks were tested and closed. We were ready for the big moment, seven years in the making and Aliza is going to float. The crane operators moved into place and gave a pull on the cable. Nothing moved. The automatic safety had kicked in when the load proved to be too much for the crane safety margins. Then the operator engaged the manual override and up she went. A few patches to paint on the keel base and she was ready for her first taste of the sea.

Aliza is lowered into the water by the crane and about to touch the Mediterranean Sea water.

Dad went aboard first while she was still connected to the crane cables, to capture the moment. I was next and went directly to the engine room to inspect the bilge for any sign of water. Things looked ok, but, ten minutes latter, I heard water. Hurrying below, I spotted it gushing in. It was startling. The bilge was filling up, and the electrical pumping system was not yet operational. Thank God for the manual bilge pump. (There’s something in what they say about a scared sailor with a bucket.) Next time I’d prefer to use an electrical pump.

We started looking for the cause of the problem, where’s the water coming from? It was coming out of the holding tank where the hose from the aft head was not connected. We checked all seacocks. In the forward head, we found one still open, allowing water to fill the holding tank and then flow after the delay into the bilge from the open hose connection. We shut the seacock, but the water did not stop completely. There was still a trickle of water seeping through the valve. This was a problem, which left us puzzled for awhile. There was no danger of sinking, but it was still a real mystery. As for the amount of water coming in, it was quite insignificant after we closed the seacock (about 1 gallon every 15 minutes). We used the manual bilge pump and gained some time for troubleshooting. Later, after a closer inspection of the three-way seacocks, I found a handle position, which allows water to seep through. We needed to change some of the connections and plumbing. This was not a major problem, but showed us that even a simple part like a selector valve / seacock could cause problems. Murphy had made his first strike of an on-going list of near disasters.

After resolving this problem, we tied Aliza to a floating dock / barge and started working on her electrical systems, engine, and steering. We had but a few days to prepare her for the official ceremony and party. We invited friends, relatives, and neighbors to officially bring Aliza back into our family. We completed most of the tasks and were ready for the presentation and unveiling of her name.

Moshe Schwartz is holding the Aliza name plate minutes before we secured it to the side of Aliza.

The party was a huge success when about 250 people showed up and had a great time. Everyone was amazed with the outcome of Moshe’s work and all wished us the best of luck on our future adventures.

It took us another year of work to bring Aliza to a ready state for our first big trip to France. We had opted not to ship the masts and sails to Israel, due to cost of freight on a 57′ mast. We decided to use a temporary stainless steel mizzenmast for the radar and wind instruments, a wooden main mast, and bought two used sails (a Main and a Genoa) to complement the engine during our voyage. The proper masts and sails were waiting to be installed by a crew of expert French riggers.

We think our mother would be proud of her namesake and is watching over us.

There were many adventures experienced on Aliza, and Efraim is in the process of documenting them for publication. This is the first article (published in ATN Sea, Yachts and the Leisure Life Magazine in Issue # 9 July-August 2005) and is the “short version story” of the build phase.